Leadership in Ancient China

“A leader is best when people barely know that he exists.”

– Laozi

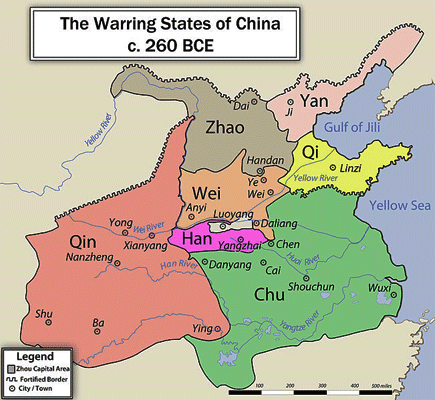

Ancient China was long dominated by the Zhou dynasty, when it fell into some 200 years of the ‘warring states period’. It was a long time of battles and conquests among seven larger states of the former kingdom of Zhou, which ended in 221 BC, when Qin Shi Huang had conquered all other states and became the First Emperor of the then united China. The Qin had invested hugely into an industrial production of their weaponry to conquer their competing neighbours. After their victories, they needed something else to unite the new empire.

Qin Shi Huang started building the Great Wall to protect against northern nomadic invasions, he built and maintained a network of transportation highways between major agglomerations, and he wanted to induce a common culture in the freshly united Chinese Empire. His regime was full of rigidity and brutality – what was not Qin, had to obey or vanish. While thousands lost their lives, this dictatorial government produced one asset for future generations: a united China, larger than it had been in the Zhou dynasty before. Yet, the Qin did not reign long, they were succeeded only 14 years later by the Han dynasty in 206 BC.

The main difference between Qin and Han can be seen in two remarkable findings. By shere coincidence, a Chinese farmer found in 1974 the first parts of the now well known terracotta army of life-sized warriors and horses, meant to protect Emperor Qin Shi Huang against the souls of those he fought in his unification wars. This huge army of tens of thousands different terracotta figures was to protect the afterlife of the Emperor in his still uncovered area of his own tomb, erected on a miniature model of then-China with real mercury to represent the Chinese rivers.

Recently the site of Emperor Han Yan Ling was opened and brought a different kind of terracotta pieces, smaller two-foot-high models which gained more flexibility from an invisible wooden arm construction, well covered by expensive satins. The Han dynasty could focus more on the arts and culture than the Qin, they also left room for less rigid philosophies, which allowed a different form of leadership as well.

“An empire can be conquered from the horseback, but not ruled from a horseback.”

– Lu Jia, Xinyu

The shift of power from the Zhou dynasty and the Warring States to the Qin Empire was a time of great cultural and intellectual expansion and it gave birth to a variety of philosophies, later known as the Hundred Schools of Thought, Let us have an eye on the main ones:

Confucianism sees the governmental structure and its relationships as given fact. Ethical values are then the training ground for humans to play the best role in this organisational system. The Confucian Classics teach an ideal behaviour within this fixed set of a socio-political order.

Legalism takes the human nature as weak and selfish, which needs discipline coming from a strict external framework. Legalism became the Qin state philosophy, which stabilised autocrats by the concepts of Shi (legitimacy of the leader), Shu (use of tactics to maintain power), and Fa (written law).

Taoism (which is the school of Laozi) draws a bigger picture, man and society are embedded in a nature that has its own implicit rules. The central value of Taoism is Ziran (naturalness), which is associated with spontaneity and creativity after freeing oneself from selfishness and desires. The basic virtues of Taoism are the three treasures of Ci (compassion), Jian (moderation) and Bugan Wei Tianxia Xian (humility – not daring to act as the first under the heavens). Taoism disposes of the concept of Wu Wei (effortless action), by which the Wise comes into harmony with nature in its entirety.

Moism takes the individual competencies in consideration when thinking about a best fit in leadership positions. Founder Mozi believes in talent and meritocracy and believes in love as the guiding principle which rulers derive from of Heaven. The measure of a Moist populations wealth is sufficient provision and a large population instead of any other individual goal. Moism did not survive the Qin dynasty.

If we come back now to Laozi (aka. Lao Tze or Lao Tzu) and his famous verse 17 of the Tao Te Ching, it now gains a different understanding!

Here we first see it in its accurate English translation:

太上,下知有之;其次,親而譽之;其次,畏之;其次,侮之。信不足,焉有不信焉。悠兮,其貴言。功成事遂,百姓皆謂我自然。

(The unadulterated influence)

In the highest antiquity, (the people) did not know that there were (their rulers).

In the next age they loved them and praised them.

In the next they feared them; in the next they despised them.

Thus it was that when faith (in the Dao) was deficient (in the rulers) a want of faith in them ensued (in the people).How irresolute did those (earliest rulers) appear, showing (by their reticence) the importance which they set upon their words!

Their work was done and their undertakings were successful, while the people all said, ‘We are as we are, of ourselves!’

Or in the words of the often quoted proverb:

A leader is best when people barely know that he exists, not so good when people obey and acclaim him, worst when they despise him. Fail to honor people, They fail to honor you. But of a good leader, who talks little, when his work is done, his aims fulfilled, they will all say, “We did this ourselves.”– Laozi